Yesterday, evening, the U.S. CDC published its second monkeypox technical report. The report includes analyses from the Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics, a brand new center where I worked until recently. I have admired the technical reports that UKHSA publishes, and this latest edition from CDC is just as thorough and informative. Congrats to the team!

Some highlights:

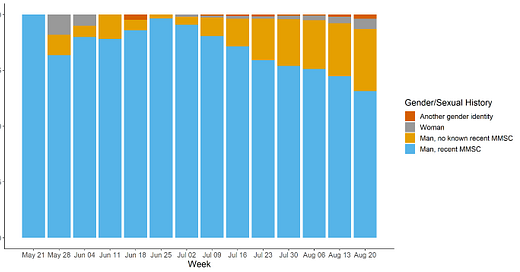

Although the majority of monkeypox cases remain concentrated in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), cases are increasingly being reported in other populations.

Men with no recent male-to-male sexual contact constitute around 20% of cases in recent weeks, and women and people of another gender identity constitute a small but growing slice. (There are also seven confirmed and 45 probable pediatric cases.) The report says:

Our current assessment for the most likely longer-term scenario is that the outbreak will remain concentrated in MSM, with cases increasing over the coming weeks, but falling significantly over the next several months. We have low confidence in this assessment. We note that low-level transmission could continue indefinitely, and the cumulative number of cases that could occur among MSM is unknown.

To me, the increase in cases in people without recent MSM sexual contact is concerning. I can think of two possible reasons: either the virus is moving into new populations, and/or ascertainment (finding cases) has improved in other groups over time. Edited to add: A third hypothesis that could explain the trend is a changing willingness to disclose sexual history.

Test positivity by demographics would help to shed light on what is behind this trend. Overall test positivity has been hovering around 20-25% for the last month, which I think is probably still too high.

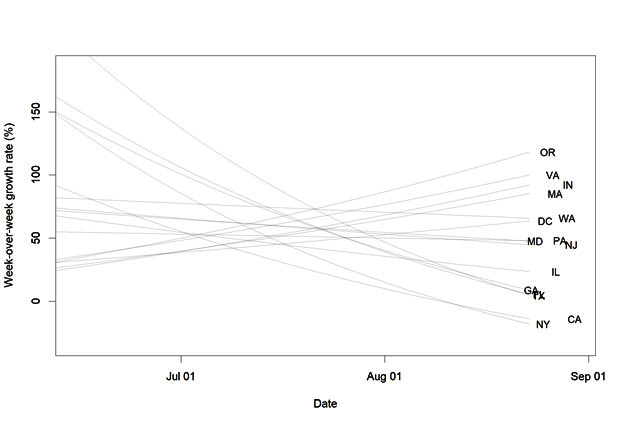

The outbreak is slowing. Doubling time of the outbreak has slowed from 8 days to 25 days, though there are uncertainties due to reporting delays and missing data. This is similar to trajectories seen in Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom and Canada.

The technical report “[assesses] the monkeypox outbreak in the United States will most likely continue to grow very slowly over the next two to four weeks, likely with a declining growth rate.” This seems right to me. We are turning a corner (at the national level, at least) but we’ll need a more concerted plan to get to fully squash transmission.

However, as I theorized in an earlier post, those improvements are not evenly distributed across states. Case counts in large, populous states like Texas, California, and New York that were hit early in the epidemic are slowing just as other states like Oregon, Virginia, and Indiana begin to pick up steam.

Demand for the vaccine may also be slowing. For the 30 jurisdictions that have reported data on vaccine administration, the number of first doses given has dropped week over week since August 7. Usually, that would reflect a decline in demand, but this was around the time when the administration switched to a dose-sparing strategy that relies on intradermal administration (though not all jurisdictions made the switch right away) which makes the trend a bit difficult to interpret. Did everyone who wants the vaccine or has ready access already receive one, or are there challenges related to demand or administration of intradermal? I hope it’s the former, but it would be good to better understand what’s happening on the ground.

The vaccine administration data also highlights the gap between who is most affected and who is being vaccinated. The week of August 27, 38% of cases were in people who are Black or African American, and 29% were in people who are Hispanic or Latino. However, Black and Hispanic people have received 12% and 25% of vaccine doses, respectively.

CDC has dramatically accelerated data sharing. The report also contains information on scientific studies that CDC is conducting to learn more about the virus. I was impressed to find that preliminary results are included for two of those studies. The abbreviated conclusion is that CDC was able to find some evidence of missed infections in serum and residual swabs, but it’s not common (2-4 of 181 serum samples and 2 of 213 swabs taken for other purposes were positive).

Normally, the epidemiological analyses and results from scientific investigations would be shared in a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, if they were shared at all. That mode of communication has its place, but I find this to be an enormous improvement in timeliness and detail. Experts in state and local health departments, academia, and health communicators can all draw from this information to help shape their own work, which in turn will contribute to the cause of slowing transmission.