Outbreak data this week

Monkeypox, pediatric acute hepatitis and Ebola

An incomplete list of outbreak data and reports that caught my attentions this week.

Monkeypox

Disparities: Washington DC and New York City recently joined North Carolina and Georgia in sharing data on both cases and vaccine administration by age, gender and race/ethnicity. Most striking is disparities by race. In all four locales, Black men are disproportionately affected by monkeypox, yet they have received comparatively few vaccinations.

For example, people identifying as Black (mostly men) constitute 37% of cases in DC, yet only 21% of vaccinations. The disparity is even more stark in North Carolina, where 70% of cases and 26% of vaccinations are in Black men. In Georgia, it’s 71% and 45%. New York City comes in at 25% and 12%. New York also makes an additional data point available—Black men make up 31% of the population eligible for pre-exposure vaccination.

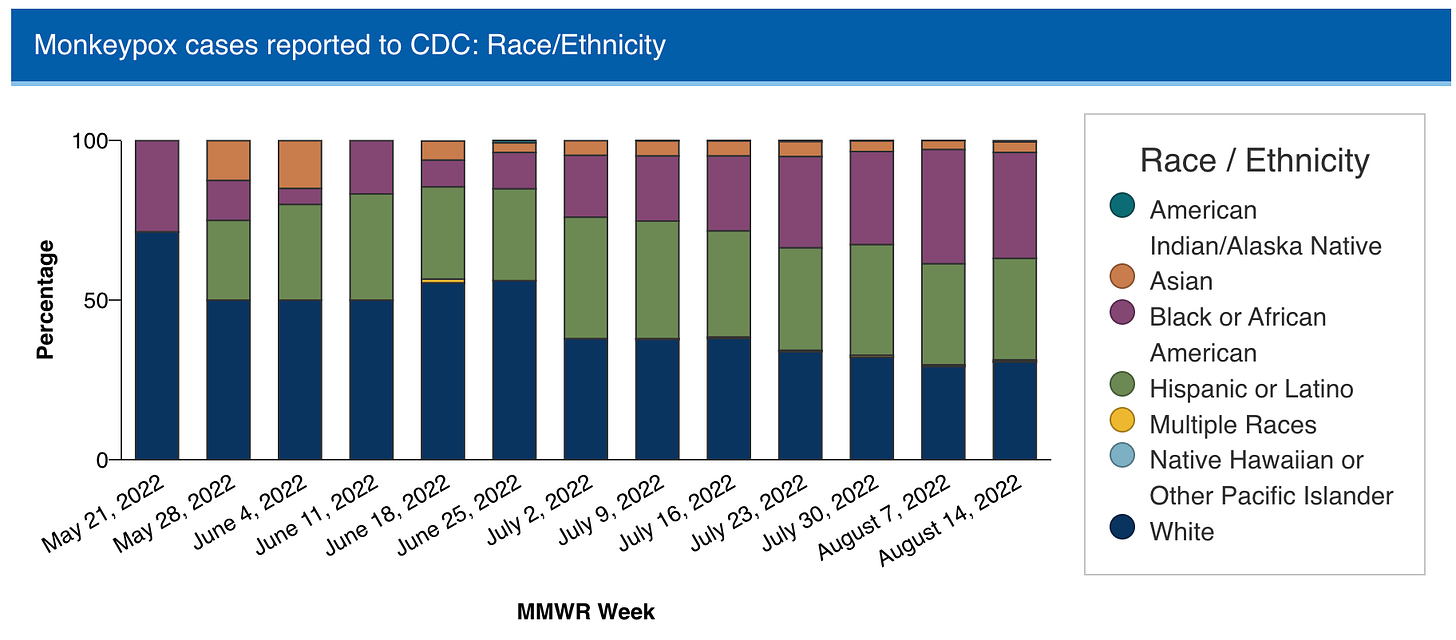

At the national level, the share of cases that are in people of color is increasing over time. We know this because CDC made new data available yesterday on the demographics makeup of cases.

These data reveal an urgent need to tailor the outbreak response to ensure Black men have access to vaccinations, treatment, testing, educational messaging, and resources for supported isolation. More jurisdictions should also collect and share this data so that these important gaps do not go unobserved and unaddressed.

Testing: As I have written previously, testing is an important lens for understanding case ascertainment. The total number of tests run has increased week over week, reaching over 16,000 the week of Aug 13. Test positivity has come down to 25%, which I take to be a good sign. There was also a slight decline in the number of positive test results, which is an even better sign. I hope to see those trends continue in the coming weeks.

UK trends: The UK Health Security Agency published a new monkeypox technical report—their sixth! The report confirms that case counts there are declining, and that men who have sex with men continue to be the population at highest risk, representing 97% of cases for whom data is available. I think we will likely start to see similar trends in the US at the national level soon. (More on whether the monkeypox outbreak has peaked.)

Pediatric acute hepatitis

This outbreak has been a puzzler. First, a short background. Last fall, clinicians in multiple countries reported seeing an uptick in the number of previously healthy children who developed hepatitis. No obvious cause was found, so epidemiologists launched a series of investigations into what is causing the severe liver disease. The leading suspect is adenovirus, a common virus that can cause a range of usually-mild illnesses from gastrointestinal illness to a regular cold.

Now on to the update. The CDC published a new technical report on pediatric acute hepatitis. It contains a rare good news story—the outbreak appears to have peaked in May, and cases are down considerably since then. In the United States, the tally currently stands at 358 cases, most under the age of 5. Some children, about 6% at last count, required a liver transplant and 13 have died. Of the 299 patients under investigation with an adenovirus test, 45% were positive.

According to the CDC technical report, multiple surveillance sources do not show an increase in pediatric acute hepatitis trends at all, leading some experts to wonder whether this event is an outbreak at all. We’ll have to wait for the investigations to unfold to learn more.

Ebola virus disease

Officials in the Democratic Republic of Congo reported a new case of Ebola virus disease in Beni. Scientists have already released a genomic analysis linking the case to a 2018-2020 outbreak. They hypothesize “transmission of Ebola virus from a persistently infected survivor or a survivor who experienced a relapse.” Two hundred doses of Merck’s Ebola vaccine have been mobilized to help with the response.

It’s astonishing how quickly this analysis was completed and publicly released. Genomic epidemiology consistently leads the way on open outbreak data which I would love to see more of in other areas of outbreak science.

Thanks for the summary. You've just made the summary I've got to do for my organization a bit easier!