This week, I teamed up with Katelyn Jetelina, author of Your Local Epidemiologist, to discuss what’s behind a recent increase in respiratory disease in kids. Your Local Epidemiologist is a newsletter covering topics like COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, mental health, and women’s health. Also check out our previous collaboration on pox vaccine ACAM2000.

Emerging infectious diseases like monkeypox and polio capture many headlines, but parents of young children know it’s the “normal” viruses (now including COVID-19) that disrupt our daily lives the most.

These common respiratory viruses are on the rise among children. Last week, the CDC alerted clinicians to a surge in severe respiratory illness in children. Anecdotal evidence of busy hospitals is peppered across social media, too.

Why might this be? And what are we seeing in the data?

Impact of the pandemic

Our kids encounter innumerable viruses every day. At day care. At the grocery store. At home. Viruses like RSV, rhinovirus and enterovirus usually cause mild, cold-like symptoms, but they can cause severe disease, too, especially among children who have never experienced the virus before. For example, RSV is typically not given the attention it deserves, but has an annual hospitalization rate of 2,300 per 100,000 children under the age of 1. (In comparison, the estimated hospitalizations rate is 30-40 per 100,000 children for flu and 48 per 100,000 children for COVID-19, pre-vaccine.)

The measures we all took to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2 also worked on all the other viruses. This was an enormous benefit that likely saved hundreds of lives. For flu alone, the number of pediatric deaths fell from 144 and 199 in 2018 and 2019, respectively, to just 1 in 2020. Deaths were also averted from RSV, adenovirus, and other common pathogens. The drawback is that the population immunity normally maintained through regular cold and flu seasons eroded, leaving more people (especially kids) without recent immunity. Experts have been warning that this creates the conditions for a severe respiratory virus season (especially flu). A resurgence of respiratory viruses is, in some ways, expected, but the timing has been uncertain. For the past two falls, epidemiologists have warned about the possibility of twin-demics.

Is this the year?

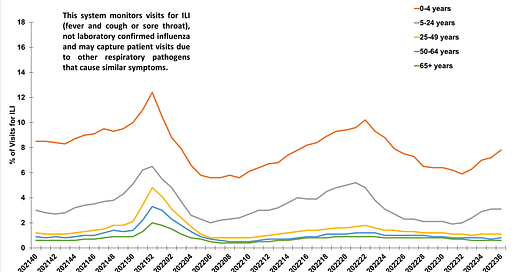

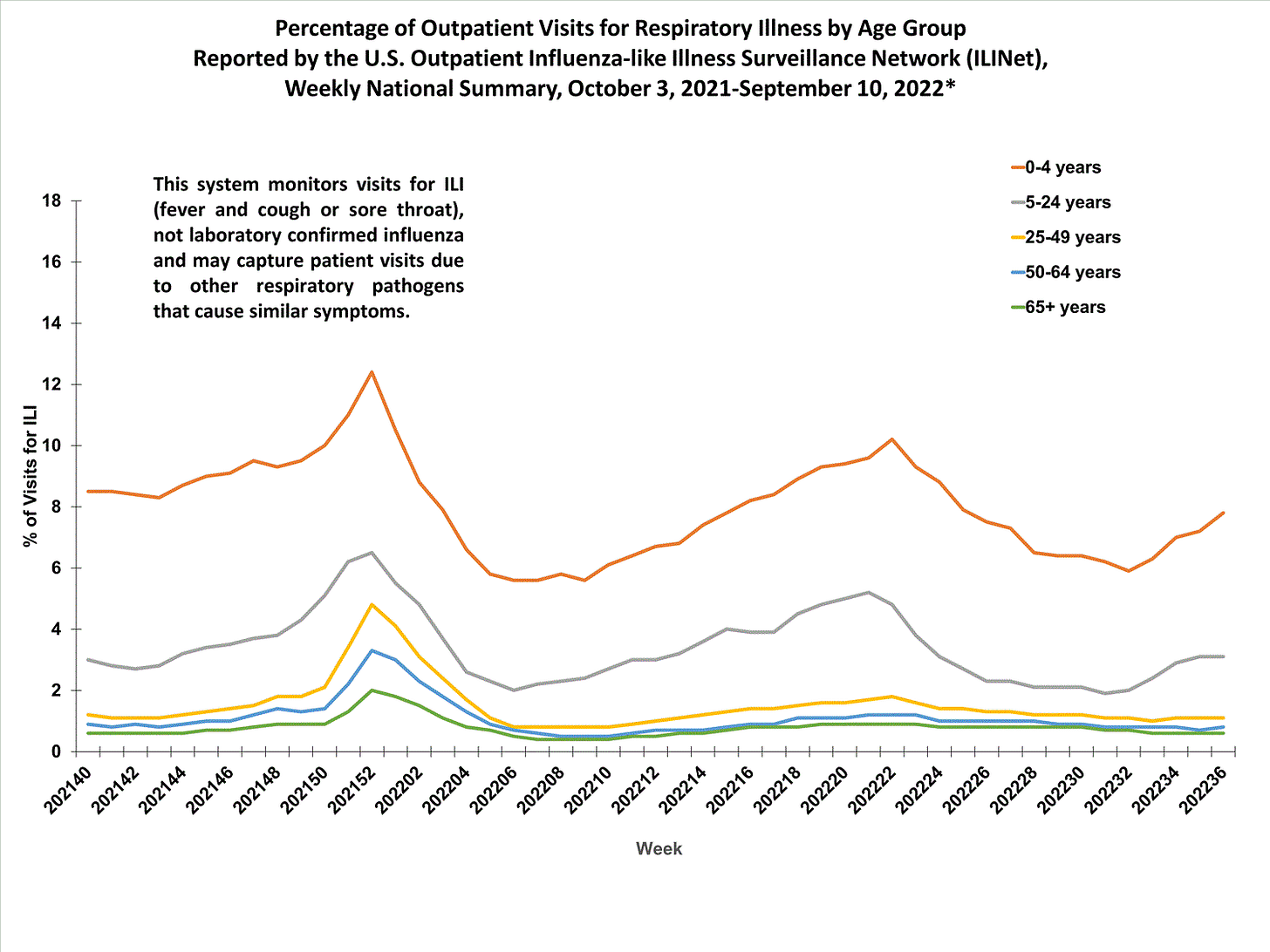

The percentage of medical visits for “influenza like illnesses” —including for symptoms like fever and cough or sore throat—is increasing in outpatient settings, particularly in children under the age of 4. It’s normal to see an increase in cold and flu illness each year, but this is occurring ahead of the normal winter schedule.

Viral activity is varying by region, which is typical. North Carolina has a spike in RSV and rhinovirus, for example, but less so in Minnesota. Chicago is seeing that about 40% of rhinovirus tests are coming back positive, and in Texas it’s more like 50%. This is high. Unfortunately, most states don’t publish respiratory disease surveillance reports outside of traditional flu season, so it’s hard to get a good look at what’s happening in each state.

Evidence from Australia, which has its cold and flu season during the U.S. summer, suggests influenza activity may now be “back to normal.” Flu activity there peaked earlier than usual, and the wave was fairly large. In New South Wales, RSV and adenovirus activity has been intense. It’s early days, but taken together, these clues suggest that this may be the year that “normal” respiratory viruses come back in force.

This season comes with another risk: Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) is on the rise. EV-D68 typically causes cold-like symptoms, and the vast majority of children fully recover, but it can result in a rare complication of polio-like paralysis in children called acute flaccid myelitis (AFM). Children with AFM may have weakness in one or more limbs, difficulty walking, and pain in the neck or back. Most require hospitalization, and about half are admitted to intensive care.

Waves of AFM appear every two years, a trend that epidemiologists first noticed in 2014. The 2020 wave was skipped, likely because the measures taken to prevent COVID-19 also prevented EV-D68 from circulating. This year, though, clinicians are already seeing an increase in EV-D68, so AFM may follow. As the graph below shows, we haven’t seen an increase in AFM yet. Cases generally peak in October and then begin to subside.

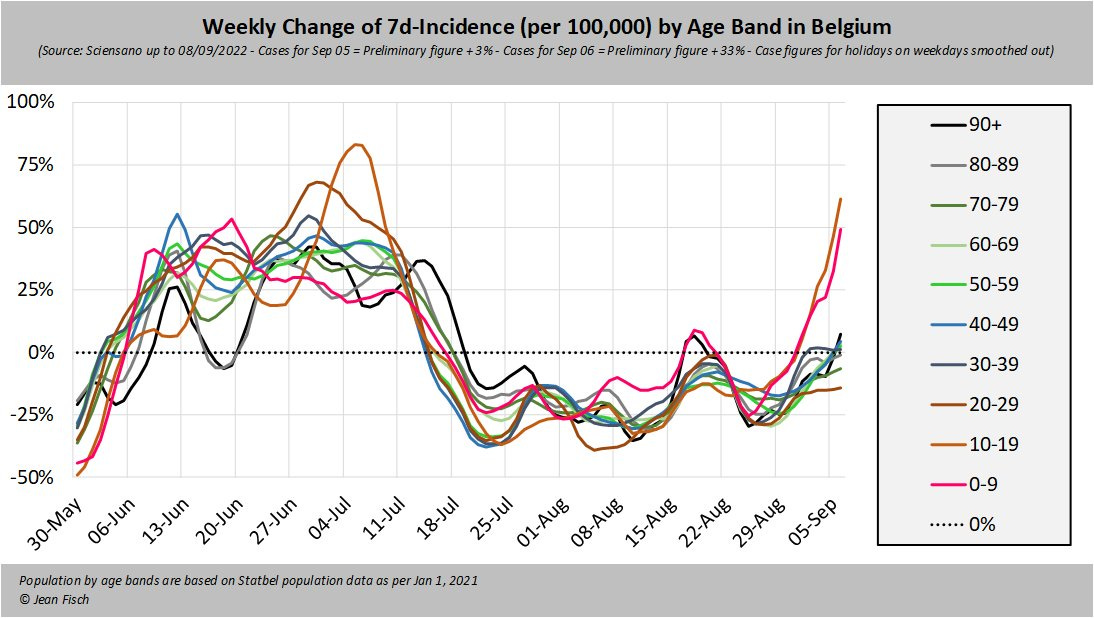

COVID-19 cases are also on the rise among children in some countries. For example, an increase is currently seen in Belgium below. If we couple this with the rise of other pediatric viruses, it’s easy to see the potential for hospitals to get overcrowded this winter.

Bottom line

Respiratory viruses are rising for young children. We don’t know if this is an early warning sign of a bad viral season, but a resurgence is epidemiologically expected. For parents, this can be unsettling and disruptive.

While we have flu and COVID-19 vaccines for children, we do not have a vaccine for RSV (yet) or other respiratory viruses. In addition to vaccinations, we can help our kids stay healthy by leveraging other layers of protection—washing hands, masking in crowded indoor settings, and improving ventilation. Most importantly, have kids stay home if they have a fever or symptoms, so we can protect other children and healthcare systems.

Love, YLE and Dr. Caitlin Rivers

“Your Local Epidemiologist” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions.

“Force of Infection” is written by Caitlin Rivers, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University and former founding member of the Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.