Monkeypox in the U.S.

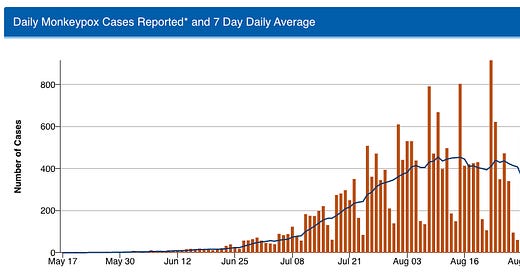

The U.S. monkeypox outbreak has slowed markedly, down from a daily average of 454 reported cases in August to around 200 daily cases now. This good news is attributable to some combination of robust communication and education campaigns, case-based interventions like contact tracing, isolation and quarantine, and the vaccination of more than 500,000 people at risk.

Still, we are not out of the woods yet. Progress on driving down case counts has stalled in recent weeks and so has the number of people receiving first doses of the vaccine. The number of tests run has also dropped off even more quickly than the number of new cases, pushing up test positivity from 21% earlier this month to 23-25% in recent weeks—a minor change, but something to keep an eye on.

For demographic trends, concerns about the virus spreading in schools or daycares have not been realized. CDC has received reports of just 35 cases in children under the age of 16. Adult men continue to constitute the vast majority of cases, over 96%. However, the racial disparities observed early in the outbreak persist. The week of September 11, Black men made up 47% of cases, and Hispanic men made up 23% of cases. In contrast, 9% and 26% of vaccine doses have gone to Black and Hispanic people (mostly men), respectively.

I have written multiple times on the need to see this outbreak all the way through to containment, including in this newsletter and for Nature and now, as things are improving, is the time to redouble commitment to stopping domestic transmission.

Ebola in Uganda

Uganda recently declared an outbreak of Ebola in the Mubende region, west of capital Kampala. As of Sunday, there were 34 confirmed and probable cases and 21 deaths, which Helen Branswell pointed out already puts it in the top 20 recorded Ebola outbreaks. The current outbreak is caused by the Sudan virus, which is concerning because the Ebola vaccines and therapeutics that have been used to control outbreaks in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (likely) do not protect against Sudan virus. There are at least six candidate vaccines for the Sudan virus, three with Phase 1 data. If the outbreak continues, we may see trials for those candidate products stand up shortly.

Of note, the World Health Organization has assessed the risk of this outbreak to be high. (Text from WHO but I changed the spacing to improve readability.)

According to the information currently available, the overall risk has been assessed as high at national level considering:

the confirmed Sudan virus and the lack of an authorized vaccine;

the possibility that the event started three weeks before the identification of the index case and several transmission chains have not been not tracked;

patients presented at various facilities with suboptimal infection, prevention and control (IPC) practices including inadequate use of personal protective equipment (PPE); the patients died and were traditionally buried with large gathering ceremonies;

although the country has developed an increased capacity to respond to Ebola outbreaks over recent years, and has a local capacity that can be easily mobilized and organised with available resources to mount a robust response, the system could be overwhelmed if the number of cases increases and the outbreak spreads to other sub-counties, districts and regions, as the country simultaneously responds to multiple emergencies, including anthrax, COVID-19, Rift Valley fever and Yellow fever, as well as flooding and prevailing food insecurity.

Positive outbreak news

Good news (using that term loosely here) rarely makes the headlines. Here are a few positive developments related to outbreaks.

An outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology was reported in Argentina earlier this month. Public health officials conducted clinical, laboratory, and epidemiological investigations and concluded that Legionella was to blame. Legionella outbreaks are serious because they can cause severe respiratory infections, but the pathogen does not spread between humans.

An outbreak of Marburg, a viral hemorrhagic fever similar to Ebola, was successfully contained in Ghana. The outbreak was first confirmed in July and was declared ended earlier this week. The final tally was three cases and two deaths. Outbreaks like this are declared over when two incubation periods have passed with no new cases.

The BA.5 wave is finally subsiding in the United States. Case counts have fallen to an average of 55,000 reported cases per day, the lowest since April. We still have a long ways to go to reach our all-time low of 11,000 cases last summer. Hospitalizations are trending down as well.

Malawi is the latest country to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem. Trachoma is a bacterial infection that causes blindness. It is controlled through antibiotics and hygiene measures, along with surgery to treat existing disease. Vanuatu and Togo also recently announced the successful elimination of trachoma.

I like your "positive outbreak news" section, Caitlin!