Influenza activity remains low, and COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths are still falling. Of note, the end of the Public Health Emergency also means the end of several data streams, so COVID-19 is now harder to track. In better news, norovirus activity is also down, except in the Western region where it remains fairly high.

I answered a reader question for the NYT again this week. It’s a heavy one. “Is it even really possible for us to plan for the next pandemic, considering the failure of the American people in the pandemic we are currently in?” Read my answer here.

Mpox

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sent out a Health Alert Network bulletin today warning of an increase in mpox (formerly called monkeypox) cases. A cluster of 12 confirmed cases and one probable case has been identified in the Chicago area in recent weeks. Troublingly, nine of those 12 cases had received two doses of the Jynneos vaccine.

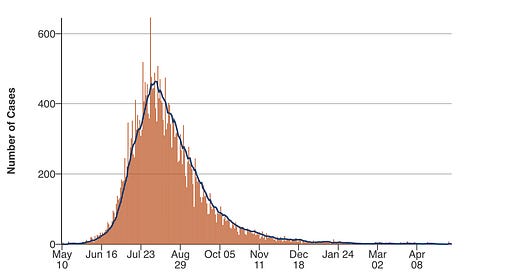

The cluster may be the beginning a resurgence after months of relative quiet. The epidemic was first recognized around this time last year, primarily in men who have sex with men. Transmission peaked in the summer months, and declined steadily through the fall and winter seasons. In recent weeks, the number of new cases dwindled to nearly zero, both in the United States and Europe. But now, with Pride month just ahead, CDC is warning that the “spring and summer season in 2023 could lead to a resurgence of mpox as people gather for festivals and other events.”

The epidemiological investigation will be key to uncovering the risk factors and drivers of this cluster. Because most of the cases had been vaccinated, the question in my mind is whether protection conferred by the vaccine is waning, and how that varies by route of administration. There are few epidemiological details specific to this cluster, but in general Jynneos administration peaked in August and September and dropped off quickly thereafter, so for many people it’s been eight or more months since they were vaccinated. That is also around the time that health officials switched from subcutaneous to intradermal administration, in an effort to extend the limited vaccine supply.

If the vaccine is less effective than hoped, either because of waning or because of the move to intradermal administration, that would suggest that the risk of a summer resurgence is high. If epidemiologists identify other reasons for the Chicago cluster, that would imply a more positive outlook for the coming months. I’ll be on the lookout for more details as the situation unfolds, and I’ll also be looking to Europe for additional data.

H5N1

Avian influenza A(H5N1) continues to circulate widely, primarily in wild birds. Sporadic cases and clusters are also ongoing in commercial poultry flocks and mammals including, most recently, opossums, foxes, mountain lions, and skunks.

Nearly 60 million commercial poultry have been affected in the United States, stretching across 416 counties in 47 states, making the epidemic a serious economic event as well as a threat to animal and human health. Discussions are underway (and have been for a while now) about whether to vaccinate commercial poultry against the virus, a decision that is expected to have heavy trade implications. Still, we are over a year into this epidemic and tens of millions of birds have been lost, to say nothing of the risk that the virus will become better adapted to humans. That discussion should be expedited as much as possible, given the high stakes.

In other news, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is updating its risk assessment for H5N1. The agency’s risk assessment is one of the ways the U.S. government organizes itself around preparedness and response. I’ll share more when the updated risk assessment is posted.

Marburg virus disease

Equatorial Guinea and Tanzania continue to fight unrelated outbreaks of Marburg virus disease, a hemorrhagic fever related to Ebola virus disease.

According to the World Health Organization, Equatorial Guinea’s outbreak stands at 17 laboratory-confirmed cases and 23 probable cases, including five healthcare workers. Of the cases, 12 of the confirmed cases and all of the probable cases have died. The cases are spread across five, non-contiguous districts. In Tanzania, eight laboratory-confirmed and one probable cases have been reported, including two healthcare workers. Six of the cases have died. Both outbreaks have been underway for several months now.

These outbreaks seem to be fairly slow moving, which I find encouraging for prospects of control. Still, the high case fatality risk is devastating, and the longer the outbreaks go on, the more likely they are to grow. I hope that both are brought to an end in the coming weeks.